81 Minutes

A few words about short movies

Every now and then, someone will come up with that most daring of film opinions: movies are too long these days. It’ll be an errant tweet by someone who just watched the latest 135-minute blockbuster, and it’ll go viral, and it’ll inspire all kinds of discussion. Many will agree. Others will say, “A movie should be as long as it needs to be.” You’ll get the inevitable attempts at factual analysis about whether movies really have gotten too long, or if that’s just our sense of it now that every Hollywood movie is a big “epic,” and weren’t epics always long? Don’t people pay the price of a movie ticket expecting bang for their buck? People will point out that most of the top-grossing movies in any given year are pretty damn long, so audiences clearly aren’t too mad about it.

All this will, of course, lead to the next stage of conversation: movies should be shorter. This is where the real fun begins. Comments will start pouring in about how wonderful it is when a movie is just 90 minutes. And good god, the bill of a movie that drops below the 90-minute mark? When a movie is 80 minutes? 70 even! “Did you know Dumbo is only 64 minutes long?”

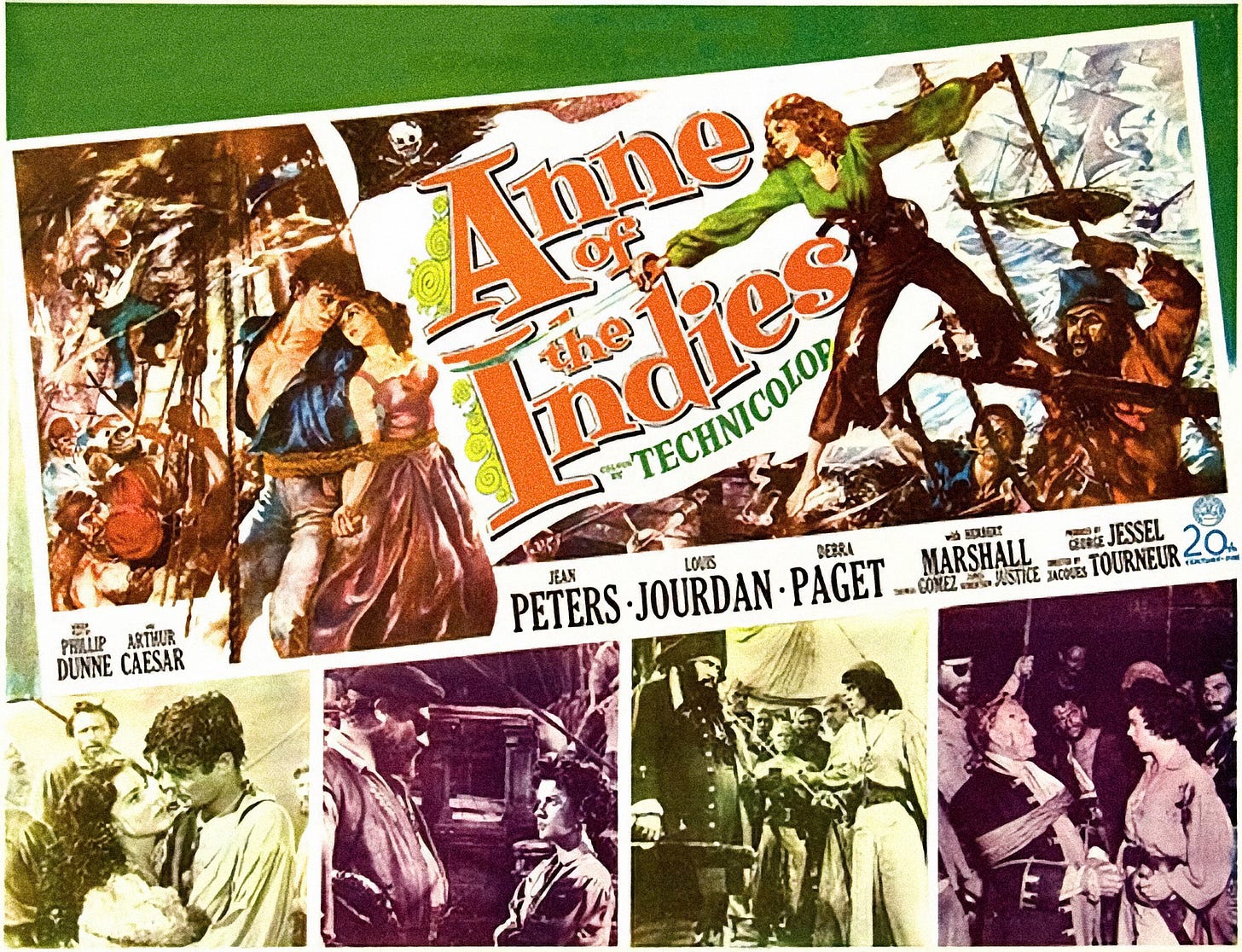

Over the weekend, I ventured out to the TIFF Lightbox for a Cinematheque screening of Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies, a great pirate movie from 1951 starring Jean Peters as the fearsome Captain Providence. It’s a thrilling, old fashioned swashbuckler and best of all, it comes in at a cool 81 minutes. But the running time doesn’t necessarily mean much. I’ve see 70-minute movies that bored me to tears. Thinking about the length of a film, it’s not so much how long it is, but what it does with the length it’s got. That idea, about movies being as long as they need to be, is obviously true from an artistic perspective, but how long they actually need to be is questionable even within those artistic considerations. The remarkable thing about a good 81-minute movie from 1951 is not that it is as long as it needs to be, but that it does an incredible amount within its short time flickering on the screen.

I hadn’t seen Anne of the Indies before, and I don’t know if the writers of Pirates of the Caribbean had seen the movie, but I couldn’t help comparing the two in my mind. They’re not exactly similar. There’s no supernatural element in the Tourneur film, first off. The fact that Pirates was inspired by the swashbucklers of old makes comparison obvious, yet there was something more specific that had me thinking about Gore Verbinski’s deliriously entertaining adventure. It was the sheer amount of plot. Curse of the Black Pearl, the first entry in the Pirates series, comes in at a lengthy 143 minutes, including end credits, but unlike some 2 hour+ movies, it’s absolutely packed to the brim with plot machinations. There are the sword fights and ship battles, but also passions, betrayals, trading of objects, more betrayals, trickery and… more betrayals. It’s unrelenting, and if I’ve got any criticism, it’s that it can be almost exhausting. The sequels, though I love them, are definitely exhausting by being both longer and even more dense in incident.

Somehow, Anne of the Indies has almost as much plot going on as the first Pirates movie, in just over half the running time. Let me run it down for you: Captain Providence seizes a British vessel, lets live a French pirate captain named LaRochelle who’d been captured by the Brits, he joins her crew, but her first mate Dougal doesn’t trust him, and then they meet her old mentor Blackbeard who also mistrusts LaRochelle, and Anne and Blackbeard have a friendly sword fight, and then Anne ventures off, falling in love with La Rochelle, but Blackbeard shows up and reveals he recognizes LaRochelle as a French naval officer, but the Frenchman claims he was dismissed from the navy, but Blackbeard tries to cut him down, which leads Anne to slap him and send the great pirate packing, making him an enemy for life, and then some months pass with Anne and LaRochelle falling more and more in love, and they soon dock off the shores of Jamaica where LaRochelle ventures to Port Royal undercover, but in a stunning reveal, it turns out he’s been working for the British, who had captured his ship, AND he’s got a wife and has only been pretending to be in love with Anne, which is when we also learn that he’s made a deal with the British to go undercover as a captive under the wretched Captain Providence (who the British don’t believe is a woman) in order to have her captured, at which point he’ll get his ship back, but despite not having captured her, a British aristocrat offers LaRochelle is his ship back in return for posing again as a pirate captain with a pirate crew, but Dougal has been spying and reveals LaRochelle’s treachery to Anne, who has the Frenchman’s wife kidnapped, and takes her to an island of Arab slave traders, but the slavers send them off upon learning LaRochelle’s wife is a kidnapped white woman and her husband is hot on their trail, a ship battle ensues in which LaRochelle’s ship is destroyed and he is captured, but rather than kill him outright, Anne maroons the husband and wife on a tiny islet with no food or water or even a gun to kill themselves, but as Anne sets sail she sees Blackbeard’s ship heading toward the islet to take the Frenchman, and in a turn of heart she confronts Blackbeard in another big battle that she knows she’s going to lose, all so LaRochelle and his wife can escape, and of course Anne dies at the end because this is a Hayes Code movie.

All of that happens in a span of 81 minutes, and I didn’t even mention the treasure map or the British doctor who comes to deeply respect Anne Providence or the hilarious jaunt back to Nassau where LaRochelle antagonizes Blackbeard, shoots a guy, and makes a deal with a deaf old man for information on the whereabouts of Anne’s ship. There are great bits of character detail, like Anne and her brother (dead?) having been raised by Blackbeard. There’s the fascinating gender dynamics, which somehow hew the backwards social norms of the era, while still managing to challenge ideas about femininity. Again, 81 minutes. The economy of it is staggering, but this is true of many old movies with short running times.

In just 64 minutes, Dumbo is born, fucks up the circus, gets his mom imprisoned, is forced to do dangerous clown acts, becomes disillusioned from his job, gets really high, is gifted a feather that can make him fly, then learns that the feather was a placebo and he could always fly, becomes a big star and helps get his mother freed. Edgar G. Elmer’s Detour, from 1945, is a little longer at 68 minutes, and somehow manages to take the audience through a whole convoluted film noir plot in that time.

These are movies that don’t feature the quick cutting techniques we’re accustomed to in modern cinema, and as a result, scenes often feel more staid. Some viewers would even call them slow, and in some ways they’re not wrong, as these films luxuriate more in their beautiful compositions and simple setups of people talking. There isn’t that pull toward constant movement, constant action, constant bombast. Yet Anne of the Indies has everything you could want in a movie, flying at an incredible pace in pure narrative terms, building to big reveals and even bigger emotional payoffs.

I was listening this week to the new episode of Jamelle Bouie and John Ganz’s great podcast Unclear and Present Danger. They were talking about Independence Day, and Bouie kept remarking on how good the script was. He wasn’t praising it as any kind of great or deep work of artistry. Rather, it was the tightness of it, the economy of the script in setting up distinct characters, building and paying off narrative arcs, finding ways of having all the characters converge in one place with a natural inevitability. They don’t really write scripts like that for Hollywood movies anymore. It’s not so much a length issue as simple bloat. Whole scenes that are cut to feel fast, but are actually quite long and yet only serve one function at a time. Characters whose personality is defined solely by the needs of the plot, given dialogue that’s interchangeably quippy. Action sequences that go on forever but fail to create much meaning outside their attempts to impress with digital effects nonsense. There’s no economy at all. You think back to what a movie like Jaws was able to do with its ample 124 minutes, from practically being two separate films combined into one, to its numerous amazing sequences, its distinct and memorable characters. Hollywood movies have simply become less economical in every sense of the word.

Amazing, then, to go back and watch something like Anne of the Indies and witness all that it’s able to accomplish in its swift, entertaining 81 minutes. It’s proof of the power and pleasure of economy in storytelling, and an object lesson in construction a rousing adventure. Literally, the film—and others like it—should be studied by everyone from budding screenwriters to Hollywood executives. They should dig into how Tourneur and the film’s writers, Arthur Caesar and Philip Dunne, were able to pack so much into so little time, while still allowing everything enough space to breathe so that it never once feels exhausting. There’s a better cinema to be had in that.