Hitting play on a film about American presidential politics from 1964 is a bit like slapping yourself in the face. The country’s slide into fascist authoritarian politics of late casts old art in new light, though, and sometimes an examination is worthwhile. Plus, I love Henry Fonda.

A few weeks back, I attended a screening of the new documentary Henry Fonda for President. The debut from Alexander Horwath, former director of the Viennale, charts the story of Hollywood’s most presidential actor alongside the story of America itself. Making use of a three-hour runtime, the film takes things all the way back to the 1600s, when Fonda’s ancestors first arrived in America, placing him within a wider scope of American political development, reflected by and refracted through the films he starred in.

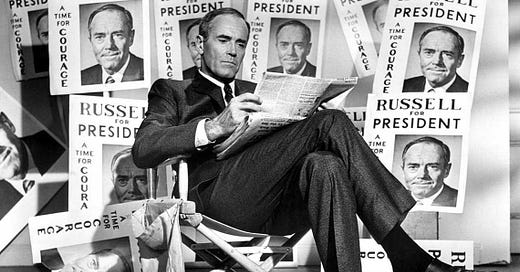

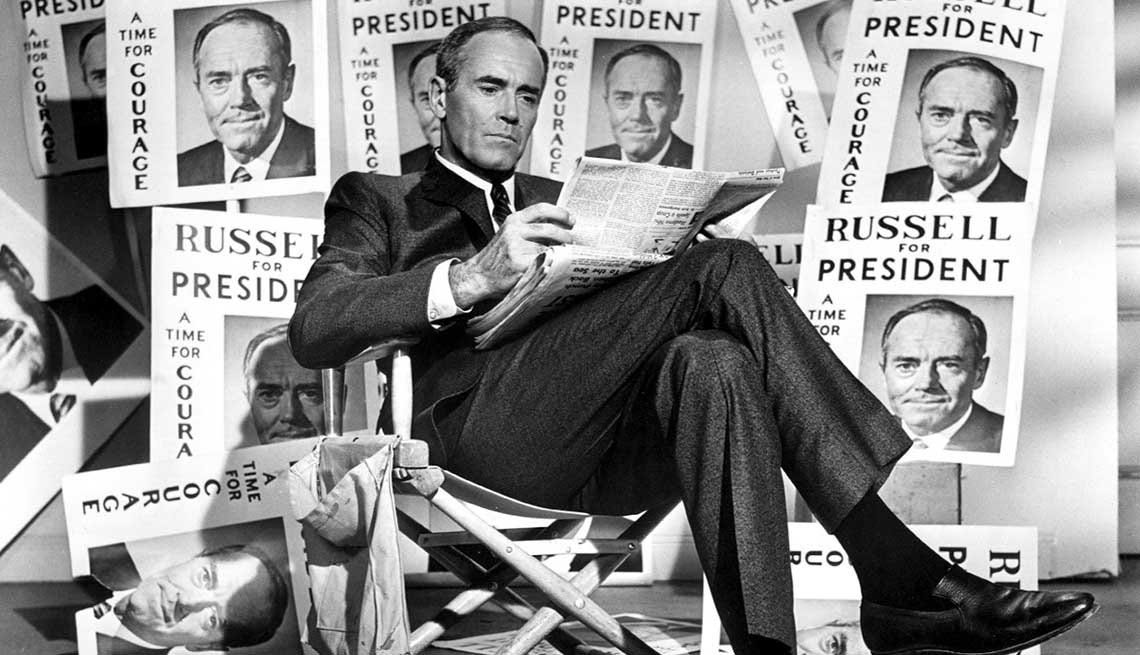

One of those films, featured quite heavily, was The Best Man, based on a play by Gore Vidal, written for the screen by Vidal and directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, who who go on to make The Planet of the Apes, Patton, Papillon, and The Boys from Brazil. It stars Fonda as William Russell, a Democrat running for the party’s presidential nomination. He’s a front-runner, alongside Cliff Robertson’s Joe Cantwell, a McCarthy-esque figure, not of typical D.C. elite breeding, indulging in demagoguery and dirty tricks. Set at a contested national convention, the drama centres on Russell’s maneuvering to win the nomination while maintaining his stoicism and integrity. Hit with oppo about the year he had a nervous breakdown, Russell is presented with material insinuating Cantwell had homosexual relations while stationed in Alaska during World War II. His decision whether or not to use the material rests on balancing a vision of moral righteousness, personally and politically, with the practicalities of political power.

The film’s ending is something of a cop out. A typical note of liberal optimism that feels divorced from the cynical realities exposed by the film. Remarkably, those realities have in some ways remained unchanged. After declaring his intention to eliminate government spending in order to eliminate the income tax, Cantwell is approached by a supporter who wants to talk about next steps: eliminating Social Security and getting rid of the “flourine” in the water.

At one point in the film, Russell and Cantwell meet to hash out the details of the homosexuality accusations. It’s a bit of an absurd scene, in that such a thing would never occur that way, but it’s dramatically exciting, a bit like the diner scene in Heat. The two heavyweights of the story, face-to-face. As Cantwell systematically dismantles the strength of the evidence against him, he inadvertently reveals something truer and uglier about him than any closeted sexuality. He’s a disloyal person, it turns out. The accusation made against him, it turns out, came from a lieutenant he’d reported himself. A colleague and friend, perhaps even a lover. In Fonda’s eyes, there emerges a recognition of the kind of man he’s dealing with.

Later, when Russell tanks his own nomination in order to stop Cantwell, the two have it out again. “I don't understand you,” says Cantwell. “I know you don't,” Russell responds. “Because you have no sense of responsibility toward anybody or anything. And that is a tragedy in a man, and it is a disaster in a president.” Russell, like many a great Henry Fonda, stands on a hilltop of saintliness. His belief in justice is serious, even as he stares into the abyss of a world that shares no such values. “You don’t understand me,” Cantwell tells him. “You don’t understand politics. You don’t understand this country. The way it is and the way we are. You’re a fool.”

I do not think Russell, in Vidal’s imagining, is a fool. Nor do I think Fonda plays him that way. Nor do I think he is a fool, necessarily. The plot is conveniently tilted in his favour—ideologically, temperamentally—so he cannot be the fool. Still, there’s truth in what Cantwell says, that the well-bred, highly-educated Russell fails to understand America’s relationship to power. That there’s a yearning in the national spirit to wield destiny, whereby individuals can express power over the world and over others, to become masters of their domain. Morality ceases to have meaning, and there’s no cogent ethic to attach oneself to other than personal ambition. What to do with a country whose political identity is wrapped up in what is, fundamentally, a corrosive vision of humanity?

In Henry Fonda for President, Horwath argues that Fonda, as a person and a figure, represents the admirable qualities of the American political spirit. The kind of person who should have been president, except that those same qualities made him both uninterested in and ill-suited to the role in reality. What then of reality? The Best Man feels a bit like a relic, trapped in the amber of a post-Kennedy liberalism. Its optimism in the end is unearned in the film and unjustified by the history that’s elapsed since. But on Saturday, thousands and thousands and thousands of people took to the street across the U.S. to mobilize against the obscenities being prepetrated by the current regime.

After receiving the information about Cantwell’s alleged homosexuality, Russell takes a moment alone with Art Hockstader, the former Democratic president. Their conversation is about power, and abotu morality. “One by one, these compromises, these small corruptions, destroy character,” Russell muses. “To want power is corruption already,” Hockstader says. “Dear God, you hate yourself for being human.” Russell tells him, “No, I only want to be human, and it is not easy.” Asking where it all ends, Hockstader says only, “In the grave, son.” One hopes character emerges before the grave.