I finished From Hell last night. I’d purchased the tome, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s classic graphic novel, back in July. It grabbed me instantly, entrancing me with its dense writing and period-influenced art. I moved through the tale slowly but assuredly, combing each page to soak in the details of the work, reading Moore’s extensive endnotes to furnish my understanding of the story he was telling. Then a few weeks in, I had to put it down.

From Hell is Moore’s telling of the Jack the Ripper murders in Whitechapel in 1888, taking as its main source of inspiration Steven Knight’s 1976 book, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, which posited the murders as a conspiracy by Freemasons to cover up a royal scandal, only for things to get wildly out of hand when it turned out the assigned murderer, physician Sir William Gull, was a very special kind of insane. The book largely follows Knight’s theory of the case, but is overflowing with details inspired by or suggested by other speculations into the Ripper case, as well as the history of London, freemasonry and more. Moore’s citations seem almost endless, and the result is a kind of kaleidoscopic tour through the dim, depraved world of late-19th century London.

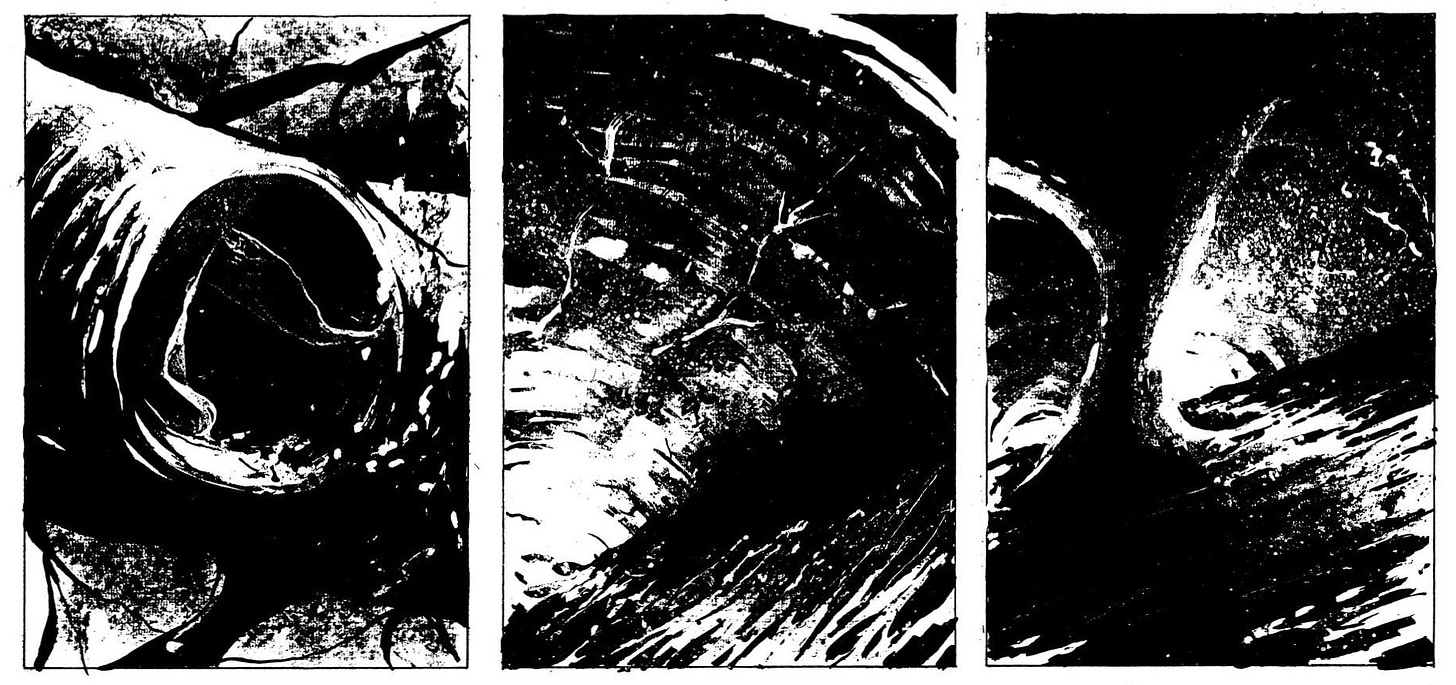

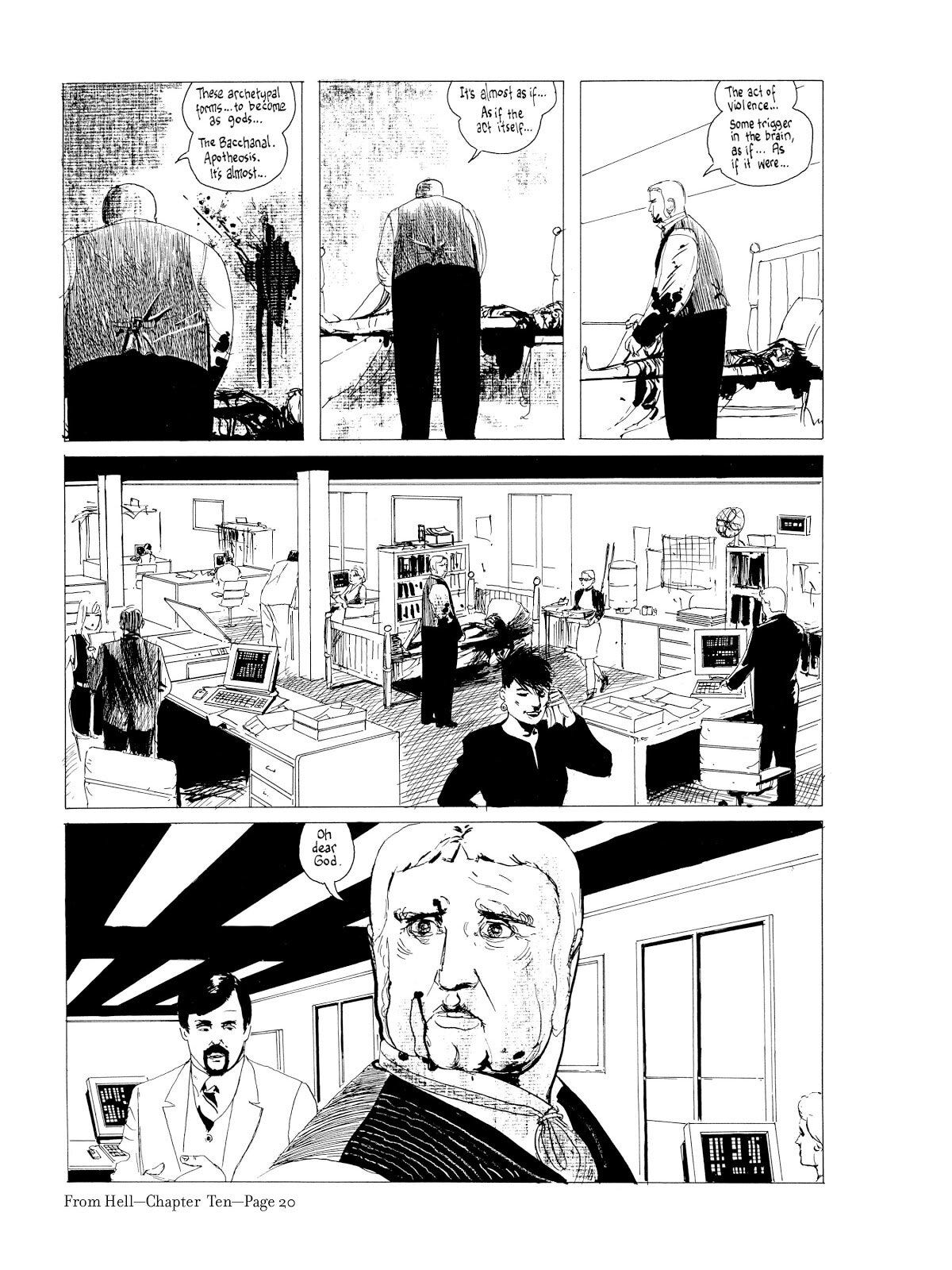

It was Chapter Ten that caused me to put the book down, for several months. In murky but graphic detail, Moore and Campbell depict the murder of Mary Jane Kelly (or, in the case of this telling, another woman mistaken for Kelly). That killing, the most infamous of so-called Jack the Ripper’s horrifying acts, was a deliriously gruesome affair, said to have lasted several hours, from the killing itself, to the full mutilation of Kelly’s body. Campbell is unflinching in his pictorial depiction of the slaying, bringing alive through his grim etchings the absolute horror of what the murderer did in his desecration. Those images serve Moore’s writing, which attends to the delirium of the Whitechapel killer, embodied in this telling by the mad physician, who experiences a terrifying transcendence through his ritualized actions that sends him hurtling across time to the present. He finds, in his act of violence, a window that cuts across eras, tearing through the very fabric of human reality, opening a wound to reveal the darkest, most depraved recesses in the pit that is our social existence.

And it was too much for me to handle.

It took several weeks for me to pick up the book once more, and having gotten over the most unpleasant chapter, I found myself able to carry on, but at a slow pace. The weight of that violence had struck so intensely as to pervade every panel, every word of Moore and Campbell’s long denouement. As the investigation into the murders carries on, and the conspiratorial coverup works overtime, the final chapters of the book distill the meaning of the carnage down to its essence: that is, it has none. There is no real meaning to be found, no insight to be gleaned. That the Gull of Moore’s story appears to find godliness in his brutality is undercut by his clear descent into basic lunacy. Nothing is achieved, not really.

It was in that late section of the book that I began thinking of other totemic works of conspiracy theorizing over culturally indelible murder. Oliver Stone’s JFK came to mind, with its barrage of supposed facts, its manic editing and formally precise messiness placing the audience in the mind of a man who believes he has uncovered truth hidden in plain sight. A cinematic masterwork, JFK nonetheless is lesser than Moore’s achievement for the simple fact that Stone, of course, believes the conspiracy theories he puts onscreen. Though, it is not really his belief that is the true limitation, for that is the prism through which he managed to craft such an incredible, influential work. No, it’s his apparent conviction that to find a grand answer, one that explains the death of Kennedy and Camelot, is itself a necessary good. That it will somehow be world-changing. The blinders will fall from our eyes and we will be able to envision and build a better future, one that might actually honour the legacy of the slain president. It’s a worldview marked by a distinctly incoherent politics, and moreover, a facile understanding of that which actually motivates people toward community in the true sense. It is, ultimately, a hollow, valueless appeal, aesthetic impact be damned.

David Fincher’s Zodiac, from the first time I saw it, opening week in 2007, has always struck me as a kind of counterpoint to JFK, building off techniques for the assault of memory Stone had developed, but more concerned with the degradation of the individual and collective soul bred by the sensationalism and sleuthing in the wake of such astonishing crimes. Does it really do anything for Robert Graysmith, at the end of Zodiac, that he has convinced himself of the guilt of a man that, quite frankly, most experts in the case now believe is unlikely to have done it? That nothing is achieved, that the violence transforms from memory to lore, that the victims are left with nothing but absence and sorrow and fear, is what Fincher’s film suggests is the real outcome. It’s a sobering notion, one reflected more pointedly in Moore’s book.

The collected From Hell, which includes the original run of comics published 1991 to 1996, along with the crucial written appendix, also includes a second appendix, a comic published in 1998, titled “Dance of the gull catchers.” In it, Moore—again with the help of Campbell’s illustrations—offers a startling reframing of his own tale. He goes back through time, using as his visual metaphor a crowd of men running in circles with nets, trampling the ground beneath them, attempting to catch birds that may not even exist. These men represent the scores of people who have attempted to narrativize the Whitechapel murders, to make sense of them, to find culprits, to unearth conspiracies. They are the people from whom Moore himself drew the details and inspirations for his own fictionalized account, yet another trampling of the reality of those horrific events more than a century prior. He lays out in this second appendix a timeline of investigation and theorizing about the Jack the Ripper case, constantly undercutting their efforts, and by extension his own, even including himself as a target in some panels. Near the end of this extra chapter, Moore offers something like a thesis statement.

Some stories just don’t have what it takes. The yarn that eventually survives to be accepted as history will do so by brute Darwinian mechanics.

We’ll lock all the suspects in a room together. They can fight it out.

As if. As if there could ever be a solution. Dr. Grape. In the horse-drawn carriage. With the Liston knife.

Murder, other than in the most strict forensic sense, is never soluble. That dark human clot can never melt into a lucid, clear suspension.

Out detective fictions tell us otherwise: everything’s just meat and cold ballistics. Provide a murderer, a motive and a means, you’ve solved the crime.

Over the weekend, I did my duty as a cinephile, venturing to my local IMAX theatre to take in Martin Scorsese’s new film, Killers of the Flower Moon. The next day, reading this final statement from Moore, I could not help thinking about that film, and its ending, which stages a live radio play recording in lieu of a postscript, describing the events following the murders of the Osage depicted in the film. Like Moore’s coda, Scorsese’s is functionally a self-critique, and as in From Hell, Scorsese literally presents himself before the audience.

After a summary of the convictions of William Hale and Ernest Burkhart, the radio play ends with a reading of Mollie Burkhart’s obituary, by Scorsese himself. A relatively mundane remembrance, describing her years of life following the terrible crimes done to her family and her community by those white men closest to her, the director notes that it did not mention the murders. Here, in a moment of profound humility on the part of a great artist, is a statement of purpose, a recentring of focus. A tale driven by the evils fostered in one very dim protagonist by his scheming uncle is passed off, at the end, to the woman whose spirit they nearly broke and, in a fitting final image, the legacy of her people, still thriving against centuries of decimation and genocide. It’s a tragic and beautiful gesture, a more optimistic alternative to the very last panels of From Hell, which depict an exotic dancer in the present day, in the place where so much carnage once took place, before the area is set for redevelopment, further washing away the nasty reality of what took place to the realm of legend.

Scorsese’s film refuses such nihilism. Its critiques are grounded in a present that has seen movement toward an actual reckoning with not only the violence of the past, but the violence ongoing in a settler-colonial order. The ugliness in Killers of the Flower Moon is not viewed from a distance. We are forced, as an audience, to explore the practically opaque psychologies of the story’s central actors, not to find explanation or greater meaning in the violence, but toward a self-understanding. The film asks us to consider the meanings of our own position, our desires, our conception of love, our complicity. When a character voices racist ideology or racial slurs, we are tempted to think of it as improper, perhaps shockingly inhumane, but also relatively benign given the scope of the story. It’s just conversation, after all. Only Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker frequently cut immediately to acts of violence against the Osage, drawing a direct link between words and actions, challenging our impulse to distinguish separate parts of an altogether sickening whole. As Scorsese doesn’t let himself off the hook, we are not let off either. The meaning we find in learning about, in recreating, in witnessing the murders of the Osage exists well beyond the scope of the murders themselves. The facts of the case, as depicted in the film, did have an answer, unlike From Hell, unlike Zodiac, maybe even unlike JFK. Roughly speaking we know who did it. The meat and cold ballistics are right there, clear as day, the crime solved. Still, it is not soluble.