Tuesday afternoons are a great time to go see a movie. For the cheap tickets mostly. It helps when it’s a beautiful 24 ºC and sunny on the walk over to the theatre. This Tuesday, I went with my mom to see Jeff Nichols’ new movie The Bikeriders. We got popcorn and Nestea™. I liked the movie. So did my mom.

Based on Danny Lyon’s iconic photo-book about the Outlaws Motorcycle Club, the film is a fictionalized account of the rise of an American biker gang in the ‘60s. Nichols’ overtly apes and twists the structural conceits of GoodFellas to tell his story, which is narrated by Jodie Comer’s character Kathy Cross, the wife of Austin Butler’s Benny. Leading the gang is Tom Hardy’s Johnny, the third prong of a love triangle of sorts, not so much romantic as existential. Nichols leans into the romance of early biker era, and so do his characters, who find direct inspiration in Marlon Brando and The Wild One. He then slowly complicates that romance with growing tribalism and violence; the mercurial movements of gang interests superseding the more simple human desires of its original members.

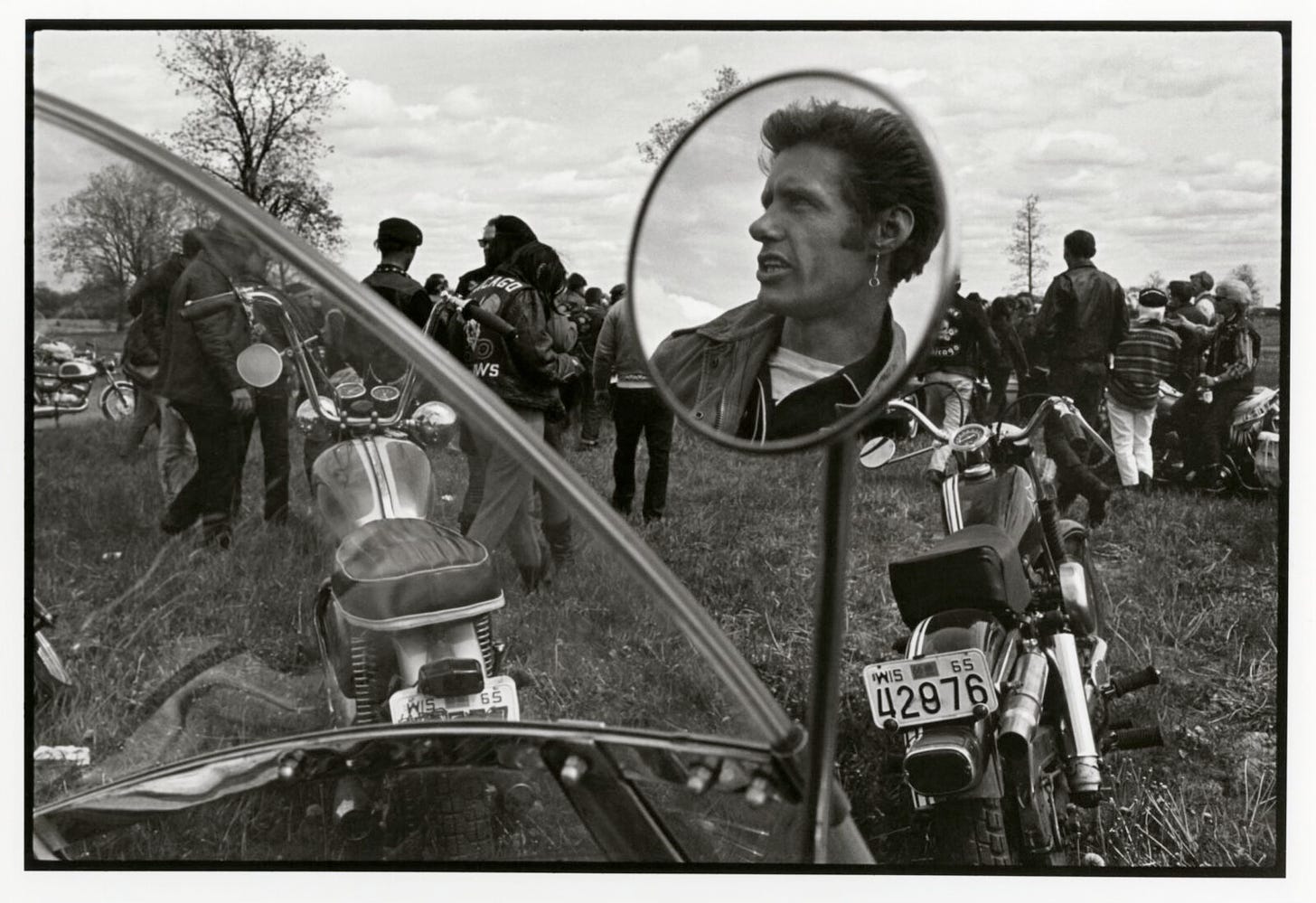

There’s something satisfying, in the year 2024, about a movie that plunges you into an interesting environment with solid characters brought to life by excellent actors. Comer, Hardy and Butler are all terrific, as are Michael Shannon, Damon Herriman, Boyd Holbrook, Paul Sparks, Mike Faist, Norman Reedus and the rest. Nichols has always been an actors director, and The Bikeriders is exemplary. It’s also the only mode at which his filmmaking really delivers. Nice, clean images aside, the movie doesn’t quite capture what Lyon did in his book. As a photographer, Lyon built an iconography. He understood light and shadow, but also the bikers’ place within the frame. In each photo, whole world of character and imagination bursts forth, and it’s no wonder Nichols spent 20 years wanting to capture that feeling in a movie. Enjoyable as the movie is, he doesn’t quite get there, more often reducing the boundlessness history and emotion of those still images by animating them and fitting them within a fairly standard narrative. The shots themselves are pretty, but missing is the majesty, and with it a real understanding of the biker gang’s allure.

One moment, though, has stuck in my mind. At the film’s end, there is a painful reconciliation. It plays, textually speaking, on two levels: an acknowledgment of the end of an era, a dream, and also a somewhat subtle confirmation of where the characters’ hearts truly lie. In that moment, one character unloads a burden and the other gains understanding, and then makes a choice to accept that understanding, however sad. Something I’ve been working through in my own life of late is reconciling my relationship to other people with their relationships to themselves. Do I just see what I want to see? What do I do when I realize my ideas about another person don’t line up with their self-conception, their desires? In The Bikeriders, the solution is a kind of settling. Into happiness, it appears, or at least something resembling it, though it may be false, or incomplete. It’s a happy ending, and profoundly sad at the same time.

We don’t walk alone in life, at least, not most of us. It is the great tension of human existence, that we must have other people to complete us, which also means coming to terms with our inability to dictate others’ interior lives or actions. It’s hard enough getting control over ourselves; to begin involving people outside ourselves in that struggle is foolish at best. So, as in the movie, we must learn to accept our lot, to accept that the people we may know and we may love may not know us or love us back the same way. There’s satisfaction at the end of that, of coming to a place where our surety in what we have in front of us, for all its lack, might still be enough to sustain us. It’s possible my own emotional difficulties are not felt by some, maybe there are fully contended people out there in the world, whose longings do not last long because they are reliably satiated. I imagine some people find that peace. But for the rest of us it’s a victory that can never be total.

The ending of The Bikeriders suggests to me the impossibility of holding on to lasting happiness. That our most heartbreaking yearnings come out of a fundamental brokenness in our nature. That even when we escape whatever ails us, and even when we find the pleasures of comfort in life and other people, we are still slave to a desire for fulfillment that can never be achieved. Not really. It’s the feeling that maybe we can never be whole, and we can’t expect others to make us so. Coming to terms with that is the only healthy way to live, but it can be soul-crushing at the same time. The image of the biker, astride a Harley, leather vest and sunglass on, is one of the greatest symbols of 20th century American freedom and individualism. Hit the road, just you and your bike, and the whole country is yours. In The Bikeriders, the growth of the club is the corruption of that Brando-esque “What do you got?” ideal of the rebel loner. It’s the myth that inspires Johnny to start his club, the Vandals, and you can see there the contradiction. The club was everything, the people in it, those relationships, that’s where all the meaning was found, and it’s also where the dream died.