People of the Watershed

A few words about having a soul

I don’t believe in God. I don’t subscribe to any religion. I’m not spiritual at all; not literally, and not in some airy, hippie, ambiguous sense either. Metaphorically, I find use. There’s no such thing as a soul, for example, but we all live with the impression of one anyway, because of what meaning is life if not to act soulfully? Of what use our actions if not with respect to the souls of others? It is the recognition in ourselves and the people around us of a “soul,” an inner “spirit,” that force of life in all its striving, that binds us together in family, in community, in society, and in civilization. To look into others and see the light eminating from their being is the great act of being human. If individualism, the product of so-called Enlightenment thinking, has any value, it is surely in the recognition not of the primacy of the individual over society, but as entreaty to society that every person be nurtured and uplifted in their individuality. To see that we are all guardians of souls in need of nourishment, metaphorically perhaps, but made concrete by our deeds.

Over the weekend, I visited the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, a public museum, owned by the province Ontario, tucked away in a wooded area on the Humber River Valley in the village of Kleinburg, some ways north of Toronto. The walk through fiery coloured trees, leaves changing as the fall weather begins to cool, is worth the visit alone. Famous as the home to an incredible collection of art by Canada’s Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven painters, the museum has been something of a constant in my life. Numerous visits as a child in school, opening my eyes to the wonders of the Canadian landscape as interpreted by some of the country’s foremost artists. Infrequent visits as an adult, but no less inspiring.

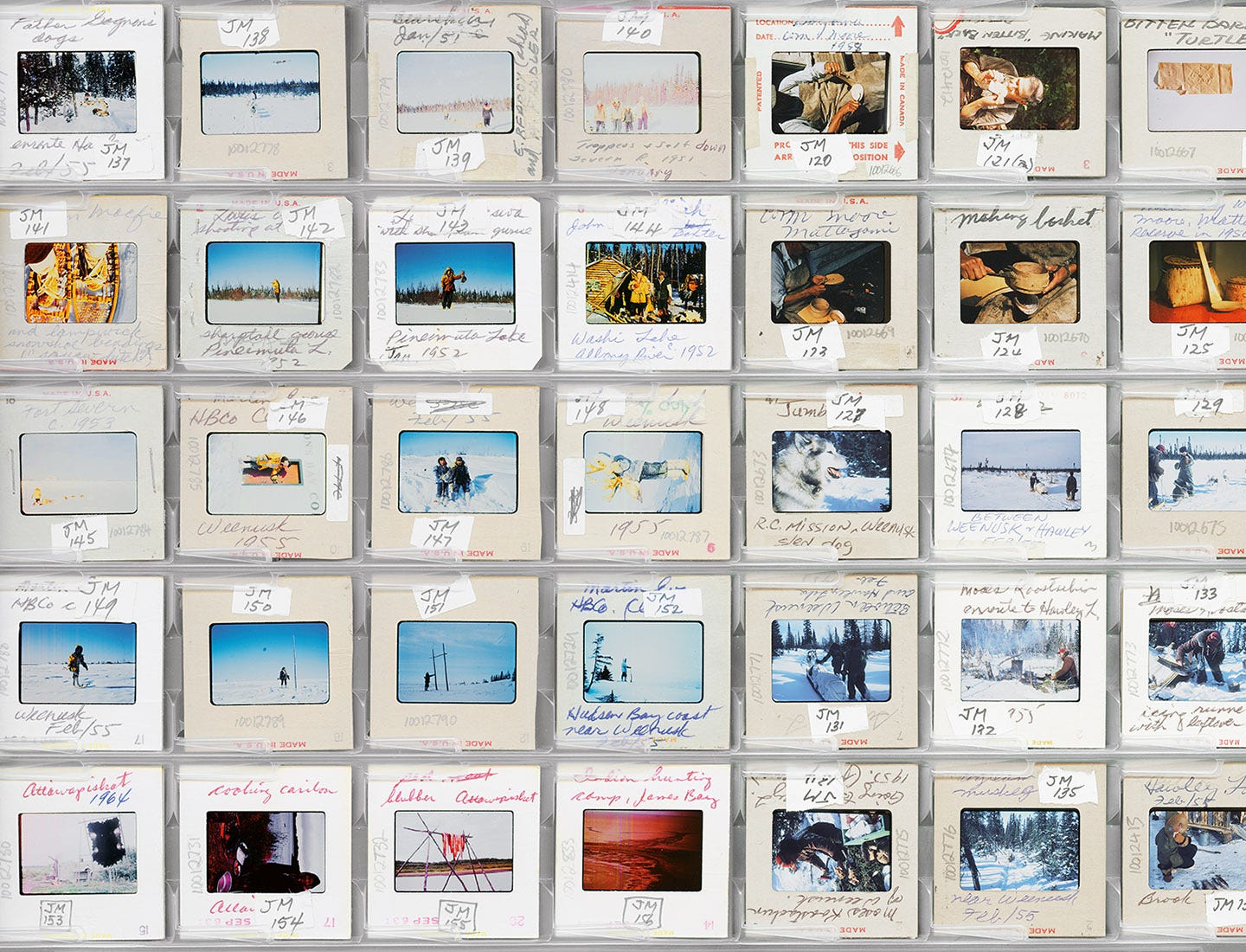

On display at the museum, amid other featured exhibitions and curations from their permanent collections, was People of the Watershed: Photographs by John Macfie. The exhibition, curated by Paul Seesequasis, a writer and journalist from Saskatoon, collects more than one hundred photographs of Indigenous communities around the Hudson Bay watershed taken by Macfie in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, when he was a trapline manager for Ontario’s Department of Lands and Forests. The photographs caught my eye immediately for their style. Unintrusive, observational, many of the photos looked like they might have been taken yesterday, but a closer look at the descriptions would reveal dates like 1957, or 1960, or 1952. The colours were so beautiful, vividly reproducing images life in Northern Ontario with unusual immediacy. Indeed, the photos were all taken on a simple Zeiss Contax, on Kodachrome slide film.

The slides were scanned—quite well, I will say, which is no easy task with reveral film—and printed on inkjet, though I will admit it would have been nice to see at least some of the slides projected, which is a very different sort of viewing experience. Nonetheless, the presentation floored me. Small-ish prints, framed and arranged around the room, not chronologically, or even by subject, but by season, which dictates so much of how life is lived, and particularly how it was lived by Indigenous trappers and their families on the edge of wilderness.

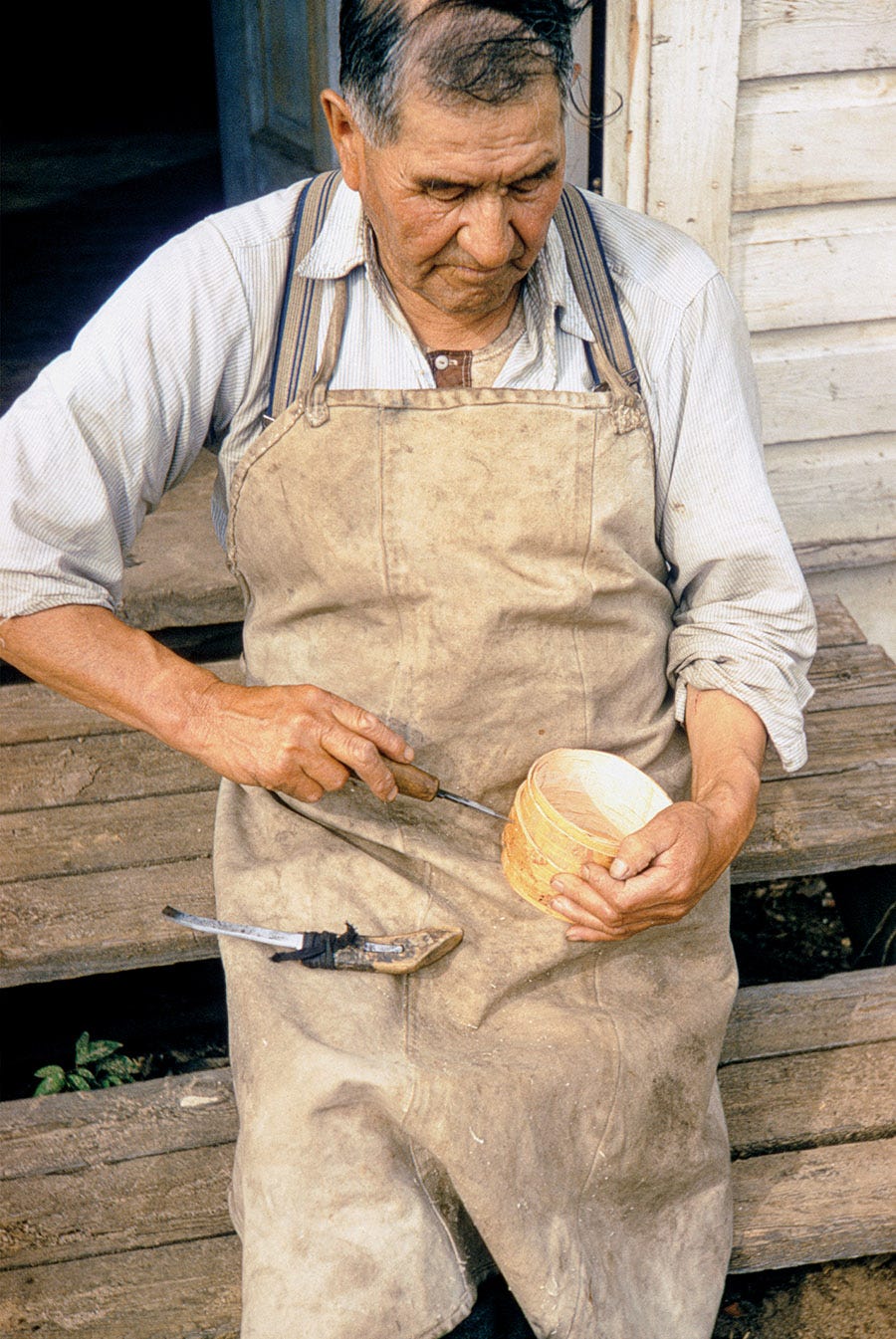

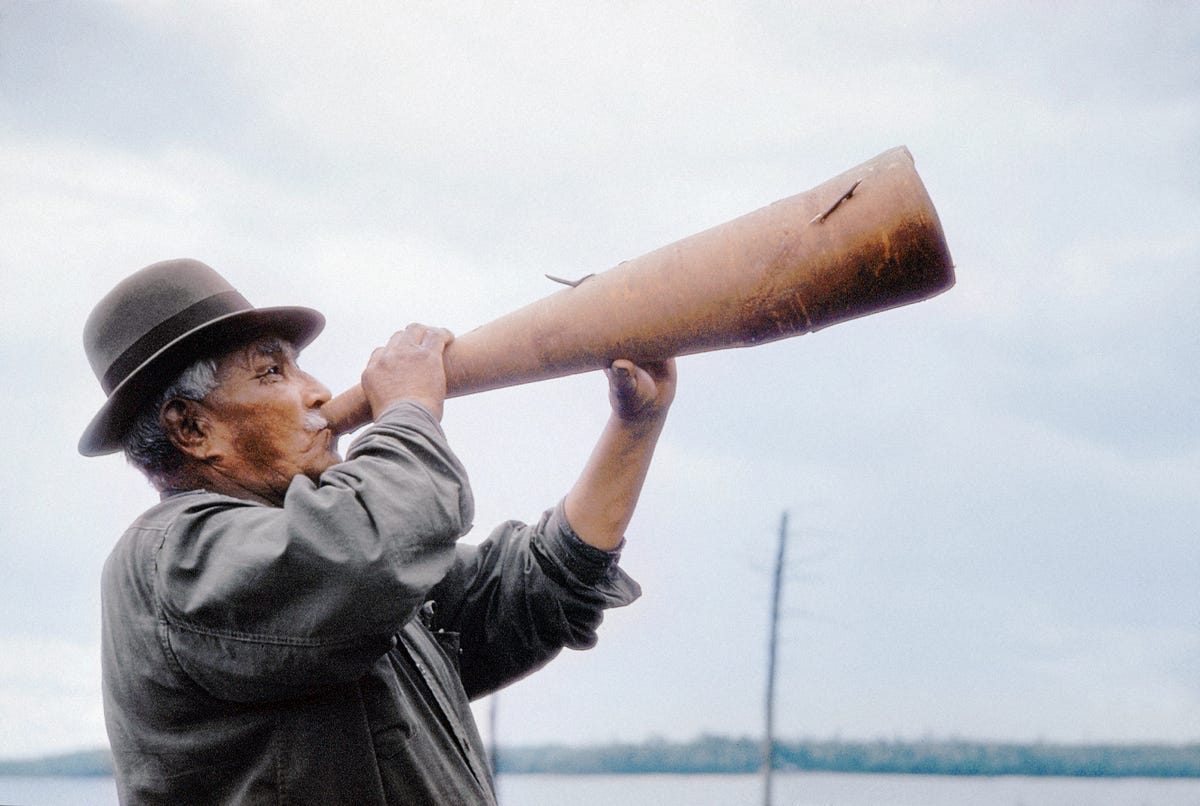

Entranced by the photos’ style, I found myself pulled in by the scenes they captured. Sometimes posed, sometimes not, what Macfie captured in his images was the daily. Kids jumping rope, women repairing gill nets, men preparing bannock, scenes of activity, celebration, communion, canoeing down rapids, rowing in regattas, crafting objects from birchbark, fixing up smokehouses, playing hockey, icing dog sled runners, and on and on. What’s remarkable is the intimacy and curiosity of Macfie’s photography. Never condescending, never imposing. His camera met people where they lived, with the observational eye of an inquisitive outsider, and the warmth of a shared humanity.

Seesequasis, who is nîpisîhkopâwiyiniw (Willow Cree), writes about Macfie’s unique photographic insight into the lives of the Anishinaabe, Cree, and Anisininew he captured in an essay for the exhibition’s companion book.

People of the Watershed is the first exhibition focused on Macfie's photographs. Seen together, they form an ambitious, wide-ranging visual account of the people, the lands, and the life of the watershed. Yet there is an intimacy here. This is the product of an attachment built over time: it feels less like an investigation and more like immersion, as if the photographer were trying to explore not only the community but also his own sense of belonging. "I do not propose to depict a time that is either better or worse than any other," Macfie writes with a typical lack of sentimentality. "The collection simply represents one moment in the continuing evolution of the lifestyle of the northern Algonquians of this region."

Indeed, the evolution of the lifestyle is another key aspect of the exhibition. Though the photos are not arranged chronologically, the period in time they capture was one of great flux for those northen communities. The remnants of an older order and older ways of life were still very present. The local Hudson’s Bay Company outlet still served as the centre for commerce and public services. The fur trapping business was still chugging along, not yet diminished by changing tastes and the animal rights movement. These were the last days, in some sense, but of course nothing just ends, and what we see in Macfies photos is a long moment of change, in which communities of indigenous people adapted themselves to a rapidly modernizing world, while maintaining their cultural identies and their attachments to places like Attawapiskat, Sandy Lake, and Mattagami. Some photos feature kids from a residential school that was built near a community along the trapline, with no indication of their lot other than their uniforms. Just kids being kids.

These photos, both in their subjects and their creation, are an expression of the soul. In Macfie’s capturing and Seesequasis’s curation we are invited to witness people in their reality, their immediate context, indulging in the quotidian, instantly recognizable, relatable. It is too often easy to view people in groups, defined by politics, divorced from humanity, blind to the soul. These are The Indians, of course, a mass reminder of Canada’s original sins, a lingering problem to be dealt with, the remnants of an incomplete genocide for which we must atone, or perhaps brush aside as something to be gotten over, depending on your political leanings. In the public imagination, these are people not often granted the benefit of humanity. In negating their souls, we destroy ours as well. These photos revivify subject and viewer alike.

Endorsing the exhibition, Anishinaabe author and broadcaster Jesse Wente writes, “John Macfie's vivid and stirring photographs show a way of life on full display - the world my ancestors inhabited and that my mom fondly described to me. It is a world that, shortly after these pictures were taken, ended. So distant and yet achingly familiar, these pictures feel like a visit home.” Though the history presented in Macfie’s photos is not personal to me, the aching familiarity is nonetheless present. They remind me of my own family, and their stories of youth, recalling the world as it was in their time and their place. Those reminiscences have taken on much more difficult meaning in my life over time, particularly in the last year, given that my parents are both from Israel.

Last night, I saw footage of people, children, being burned alive in tents outside the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Gaza. The IDF said that they had been targeting a “command and control center,” whatever that means. I try to avoid graphic videos from Gaza if I can help it, only because my own sense of impotence would threaten to turn such images into little more than objects of fetishistic outrage, or maybe self-flaggelation. Nothing useful, really. They pop up in my social media feeds as I quickly scroll past, but these ones I could not look away from. The horror, even viewed on video, is unimaginable, seemingly unreal. But it is real. Those people being murdered are real. Where is our humanity?

This morning, the New York Times published a story about the Israeli military’s use of Palestinians as human shields in Gaza. That forumlation, “human shields,” is present in the headline, a potent reversal of Israel’s claims that the killing of civilians in Gaza is unavoidable because Hamas uses its own people as shields. That such tactics by the other side, even if true, do not actually absolve Israel of its moral responsibility in deciding to kill civilians anyway is not the sort of logical analysis the country’s supports have much time for. Which makes sense when you read about Israeli soldiers using Palestinian captives as minesweepers.

After Israeli soldiers found Mohammed Shubeir hiding with his family in early March, they detained him for roughly 10 days before releasing him without charge, he said.

During that time, Mr. Shubeir said, the soldiers used him as a human shield.

Mr. Shubeir, then 17, said he was forced to walk handcuffed through the empty ruins of his hometown, Khan Younis, in southern Gaza, searching for explosives set by Hamas. To avoid being blown up themselves, the soldiers made him go ahead, Mr. Shubeir said.

In one wrecked building, he stopped in his tracks: Running along the wall, he said, was a series of wires attached to explosives.

“The soldiers sent me like a dog to a booby-trapped apartment,” said Mr. Shubeir, a high school student. “I thought these would be the last moments of my life.”

Such actions are, according to public statements by the IDF, not in keeping with their rules of conduct. They are also war crimes under international law. Yet they are done, according to the Times’s reporting, with the full knowledge of military command. The tactict isn’t new either, with the article citing similar use of Palestinians civilians to approach suspected militants’ homes in Gaza and the West Bank in the early 2000s, before their Supreme Court ruled the practice illegal in 2005. Soldiers who questioned such behaviour in the current war were met with unpersuasive justifications that mostly came down to Palestinian lives being worth less.

Two soldiers said that members of their squads, which each comprised roughly 20 people, expressed opposition to commanders. Soldiers said some low-ranking officers tried to justify the practice by claiming, without proof, that the detainees were terrorists rather than civilians held without charge.

They said they were told that the lives of terrorists were worth less than those of Israelis — even though officers often concluded their detainees did not belong to terrorist groups and later released them without charge, according to an Israeli soldier and the three Palestinians who spoke to The Times.

One Israeli squad forced a crowd of displaced Palestinians to walk ahead for cover as it advanced toward a militant hide-out in central Gaza City, according to Jehad Siam, 31, a Palestinian graphic designer who was part of the group.

“The soldiers asked us to move forward so that the other side wouldn’t shoot back,” Mr. Siam said. Once the crowd reached the hide-out, the soldiers emerged from behind the civilians and surged inside the building, Mr. Siam said.

After seemingly killing the militants, Mr. Siam said, the soldiers let the civilians go unharmed.

War is, by its nature, an erasure of humanity. It is one of the great evils, a denial of the soul, wherein people cease to exist as people, becoming something else instead. Cannon fodder. A means to an end. Like Basheer al-Dalou was when IDF soldiers used him, handcuffed and stripped of his clothes, to scout an area for Hamas fighters.

Basheer al-Dalou, a pharmacist from Gaza City, said he was forced to act as a human shield on the morning of Nov. 13, after being captured at his home. Mr. al-Dalou, now 43, had fled the neighborhood with his wife and four sons weeks earlier, but had briefly returned to fetch some basic supplies, even though the neighborhood was a battlefield.

The soldiers ordered Mr. al-Dalou to strip to his underwear, then handcuffed and blindfolded him, he said in an interview in Gaza after his release without charge.

After being interrogated about Hamas activities in the area, Mr. al-Dalou said, he was ordered by the soldiers to enter the backyard of a nearby five-story home. The yard was littered with debris, including birdcages, water tanks, gardening tools, broken chairs, shattered glass and a large generator, he said.

“Behind me, three soldiers pushed me forward violently,” Mr. al-Dalou recalled. “They were afraid of potential tunnels under the ground or explosives hidden under any object there.” Walking barefoot, he cut his feet on the shards of glass, he said.

These are scenes as though out of a nightmare, but for al-Dalou it was a waking one.

With his hands tied behind his back, he said, Mr. al-Dalou was ordered to walk around the yard, kicking bricks, scraps of metal and empty boxes. At some point, the soldiers tied his hands in front of him so that he could more easily shunt suspicious objects in his path.

Then something stirred suddenly from behind a generator in the yard. The soldiers started firing toward the source of the noise, narrowly missing Mr. al-Dalou, he said. It turned out to be a cat.

Next, the soldiers ordered him to try to shift the generator, suspecting that it concealed a tunnel entrance, he said. After Mr. al-Dalou hesitated, fearing that Hamas fighters might emerge from within, a soldier hit his back with his rifle butt, Mr. al-Dalou said.

…

That evening, he said, he was taken to a detention center in Israel. Given his experiences that day, he said, the transfer felt like a small blessing, even though he expected to face abuse inside Israeli jails.

“I was over the moon at that moment,” Mr. al-Dalou remembered thinking. “‘I will leave this danger zone for a safer place inside the Israeli prisons.’”

Speaking about his experience of ten days in Israeli detainment, the teenage Mohammed Shubeir—whose father was killed by Israeli shelling, and whose 15-year-old sister was shot and killed when Israeli soldiers entered their building—describes being forced to walk the streets of a bombed out Khan Younis, accompanied only by a drone overhead, issuing him instructions. He was made to search for the dead bodies of Hamas militants, which the Israeli military feared were booby-trapped. He was dressed up in Israeli military garb so he’d draw Hamas gunfire, like some kind of twisted game.

A few days before his release, the soldiers untied his hands and made him wear an Israeli military uniform, he said. Then they set him loose, telling him to wander the streets, so that Hamas fighters might fire at him and reveal their positions, he said. The Israelis followed at a distance, out of sight.

His hands free for the first time in days, he considered trying to flee, he said.

Then he decided against it.

“The quadcopter was following me and watching what I was doing,” he said. “They will shoot me.”

The mind reels. These scenes, as described, are simply disgusting. They are what happens when people stop viewing each other as human beings, as keepers of souls. They are the actions of people who’ve allowed their own souls to go rotten, to be destroyed, their selves given over to a war machine whose interest is nominally security, but whose true expression is little more than moral degeneracy. Zionism, support for Israel, papered with a veneer of righteousness—all for the protection and flourishing of world Jewry, of course—revealing itself as just another mode of horrendous domination, countenancing genocidal actions and crimes against humanity. Evil, in other words.

All of this has sat on my mind for a long time, especially since last October when this war began. The inhumanity breaks my heart and tears at me daily. In that context, seeing Macfie’s photos so beautifully arranged was a balm, a reminder that the soul is real, that we need only look and see the preciousness of every life. Seems banal, put like that, but what else is there?